23 Feb Michael Tullberg: The Great Rave Visual Storyteller

In This Article (Click on a section to quickly go to it)

Michael Tullberg: The Great Rave Visual Storyteller

Michael Tullberg: The Great Rave Visual Storyteller

By FeFe Greene

*This interview is older and was in our Issue 61 magazine.

Michael Tullberg has been documenting rave life through his lens since the 90s. Respectably he is the longest-running electronic music photojournalist in North America. His work helped to define the public’s opinion of the American rave scene when it was being portrayed as controversial.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, a magical underground revolution, Tullberg had been gracing the pages of worldwide publications. In addition, his work included shooting album covers for the world’s top DJs. Tullberg’s work had been recognized more than any other American photojournalist during this period.

Michael Tullberg is also the author and publisher of Dancefloor Thunderstorm: Land of the Free, Home of the Rave (2015), and editor and publisher of The Raver Stories Project (2017). These two projects became groundbreaking bodies of work earning praises from reputable peers such as VICE.

Today, Michael’s work can be found through Getty Images, red carpet shots, concerts, and celebrity benefits. He still releases articles, exhibitions, and spoken work appearances as a historian of the rave experience. During his free time, he can still be found capturing raves at their finest.

What made you choose to start capturing the rave scene as opposed to other opportunities?

In the mid-90s, I actually had a bunch of opportunities that I was taking advantage of simultaneously, in the form of photographing in several different social scenes at once. I was shooting in the industrial scene, the Goth scene, and the upscale Beverly Hills scene. As you might imagine, that’s a wide range of subject matter, which is precisely why I was doing it, because I get bored very easily.

However, towards the end of 1995, I was really becoming disenchanted with the BH thing, in large part because it was the embodiment of elitist, velvet rope L.A. club douchebaggery. I couldn’t stand many of the people in the scene.

Just imagine every clubbing nightmare coming to life in front of you—every self-absorbed, vacuous, preening macho dickhead or (Insert your own unflattering female term) you could imagine, with bottle service and cocaine thrown in. Plus, most of the music was really, really terrible. It was primarily a mix of the middle of the road, commercialized house knock-offs, and 80s mash-ups—totally unimpressive.

I basically had my antennae up, looking for the excuse to get me out of that situation. That turned out to be the rave scene, which was re-emerging following about a year and a half long police and media crackdown. So, when I saw that the scene was beginning to come back from its deep underground status, I became intrigued.

I knew that this rave thing was going somewhere. I became determined to go where this incredible scene was going, so I began cultivating relationships with the LA rave promoters. You could do that in those days, because everything was so informal and ground-level, unlike the very fixed hierarchy that exists today.

You could approach someone like Pasquale Rotella one on one, because he’d be outside a club at 4:00 AM, handing out fliers to his party that would hold maybe 1,500 people. And Pasquale was just one of many small-to-mid level promoters who were in intense competition with each other, and who were all looking for exposure. So, it wasn’t too hard for me to make the jump to shooting raves.

What was your first impression of the rave scene when you first started going to the parties?

When I first started doing raves, I immediately understood what the hell was going on in those warehouses and after-hours clubs. It was a tight-knit, grassroots community that was not only multicultural but openly embracing of that fact as well. Socially, it was the complete opposite of the Hollywood club thing, because it was based on inclusivity rather than exclusivity.

The normal social barriers of race, class, income, religion, sexual orientation—they were pointless to those in the scene, and thus were summarily thrown out the window. Much of the time, the artists were in direct contact with their fans, with the turntables right there on the floor—nothing like the massive separation at today’s EDM festivals.

It also seemed to be just about the only social scene around that wasn’t based on the traditional clubbing paradigm of getting boozed and laid. Alcohol was a very minor factor in the rave scene, and since at the time I had stopped drinking, I liked that a lot. And of course, we had the best fucking dance music in the world.

When you were photographically recording the experiences of raves in the 90s and 2000s, what did you try to achieve?

Ultimately, I wanted to bring people outside of the scene into it, visually. I wasn’t simply trying to document the scene. I wanted the viewers of my picture to be able to understand what was going on at raves, beyond simply looking at a person dancing.

Most of the photography coming out of the clubs in those days gave very little idea of what was going on in there—the music, the lights, the movement, the passion, the emotional release. Most of it looked frozen, and sterile, and boring, to be honest.

The rave scene was a classic case of sensory overload as stimulation, so the question for me became, how do I get that amazing atmosphere in the film? Yes, film—remember, this was the pre-digital era!

The answer for me was to look beyond conventional photography and take inspiration from other art forms such as painting. I actually regarded what was happening on the dance floor as great art on the street level.

Likewise, the Jazz Age is renowned for its glorious depictions of African-American social life and celebration on canvas. If legendary artists could celebrate underground dance like this, I thought, why would the rave scene be any different?

So, I began developing a visual style that emphasized the bright, swooping light and color that was normally found at raves, with some B&W thrown in. Like with the Impressionists, the emphasis was often on emotion, rather than visual clarity. If a picture had to be out of focus and abstract to get the point across, then so be it.

I crafted a series of photo SFX techniques that I could employ in the field, which would emphasize the wonderful, fluttering, proto-psychedelic vibe that was so prevalent at raves.

Why did you feel it important to become a historian of the underground rave scene?

It was important for me to become a historian for the underground rave scene because unfortunately, so few of my colleagues were doing it. There were a great number of rave writers and photographers back in the glory days of the 90s/00s rave scene, but almost none of them were putting out works about this unique period in American pop culture.

I very keenly felt the notion that the rave scene really was a pivotal moment in pop culture history. As someone who was right at the center of American raving culture during this second wave of the scene, I felt a very real sense of responsibility as a caretaker of this culture, which had not only launched electronic music in America but changed the way that parties and festivals are made and marketed.

You have to remember that until the commercial success of EDM in the mid-2010s, electronic music was very much in the crosshairs of the mainstream media, and of law enforcement as well. It’s very fair to say that the electronic music scene never got a fair shake.

The rave scene had a very bad reputation in the media during its peak, and most stories in print and on TV had a distinctly anti-rave slant, focusing with laser-like intensity on the controversies that were surrounding the scene, and not the virtues in it.

I felt that there was a real danger that some of the stories about that critical era could end up being lost to history. Worse, it could be those mainstream anti-rave people who might end up writing the “official” history of our culture. That thought turned my stomach, to be blunt.

How did you decide to present your work on the history of raves?

After some years of on-and-off planning, I decided to write my first photo book, “DANCEFLOOR THUNDERSTORM: Land Of The Free, Home Of The Rave.” Simultaneously, I shopped the book around to twenty-five book publishers that specialized in pop culture works—and got turned down by all of them. This gives you some idea of how reluctant mainstream media outlets are to touch this culture, even today.

So, I set up my own publishing company to produce and market “DANCEFLOOR THUNDERSTORM”. This ended up prolonging the gestation of the book—in the end, it took four years. Right after its launch in 2015, I began work on book number two, “The Raver Stories Project,” which is a collection of thirty memorable experiences written by people in the scene—ravers, DJs, and promoters. I published that one in 2017.

It has been heartening to see new works by people like Michelangelo Matos, Matthew Collin and others hit the shelves of bookstores during the last few years. It shows that there is an audience for works about the 90s rave scene and that there are great stories to be told from that era.

What aspects of the rave scene were you able to capture previously that you wish was still prevalent in today’s scene?

A number of things. The primary one being the genuine underground atmosphere that was so abundant in the rave scene and which is sadly so often lacking in EDM. To me, underground status goes a long way towards establishing credibility, whether you’re talking about a scene, an artist, or a song.

I miss the D-I-Y ethos. A lot of that has been lost over the years, as festivals have gotten more and more corporate. So much of the fashion looks the same because it is the same—it was ordered from the same rave gear web sites, which sell the same products, and deliver the same homogenized, sex-emphasized look that supposedly represents what electronic music culture is about. (SPOILER ALERT: it doesn’t.)

The creativity of the individual is being lost in the midst of all this, and it didn’t use to be the case. In the 90s and 00s, rave fashion was very much D-I-Y, because you couldn’t find this fashion in practically any store. You had to make it yourself, and this is what enabled the rise of kandi rave fashionistas like the Toy Ladies here in LA. They took homemade rave fashion to heights that were somewhere between celebratory and absurd. It was great.

Something else that I miss is the direct interaction between the artists and the audience. At many gigs, DJ tables were often on the floor, either on a card table or perhaps a stack of cinder blocks. Inevitably, a circle of people would gather around the tables, so that if you had a room with 500 people, only 50 of them could actually see the tables.

This meant that those outside that ring weren’t focusing on the celebrity aspect of the DJ, staring up at the stage like they do today; they were focused on the music, the visuals, and the effects of whatever they chose to enhance their senses with.

This also meant that the DJ was getting direct feedback from their audience about what music was working, and what wasn’t because the fans were right there. It was a back and forth between them, where the DJ would respond to the situation in order to keep the ravers engaged.

Christopher Lawrence and I talk about this in “DANCEFLOOR THUNDERSTORM,” and how different it is today, where the DJ is separated from their fans, hundreds of feet away on a massive stage, with pyro, dancers and stuff. How can you interact under those conditions?

Also, because the scene was so informal in many ways, it wasn’t unusual to see DJs hanging out with fans at parties when they weren’t playing. Sometimes they’d be out on the floor themselves, rocking out to whoever else was playing. That definitely wouldn’t be seen today at most festivals.

Describe the LA club culture back during the 90s and what emotions it brought on for you?

Well, as I said before, you have to differentiate LA 90s club culture from LA 90s rave culture, the two existed largely as two separate entities, with only rare interaction going on. One of the most important ones of these interactions was a club called the Bud Brothers Monday Social, which was a regular Monday night club that had a nearly 20-year run, through six different venues.

The Monday Social specialized in bringing the best established and up-and-coming talent in a mostly very cozy atmosphere, particularly during its first five magical years at a restaurant called Louis XIV.

Another vital club from those days was Magic Wednesdays, which had most of its run on Hollywood Boulevard. Magic Wednesdays were huge because not only did it feature the best DJ talent, but because it was so centrally located, it was also where a lot of Hollywood movie and TV industry people first discovered rave music and culture.

It was no accident that electronic music started popping up in commercials, soundtracks, and games soon after. But as I said, beyond these clubs, the interactions between the club and rave worlds were few.

Since the rave scene was regarded as a sort of renegade culture by many (particularly in the mainstream media, or MSM), it was that outlaw status that brought many in the scene closer together. The scene had already enjoyed a kind of “secret club” status among its members. This is one of several reasons why I often compare the rave years to the Jazz Age of the Prohibition-era 1920s and 30s.

What I remember most about the 90s LA rave scene was the overabundance of great music and talent, which you could see on a regular basis, almost at your leisure. For a period of almost ten years, Southern California became the de facto center for raving culture in North America. It was no coincidence that major festivals like EDC, Audiotistic, and Circa were all born and grown in SoCal.

We had more events and major talent here than pretty much anywhere else in the country. It was great knowing that I could enjoy great parties in the desert, on a mountain, on a beach, or in a killer after-hours around the corner.

The number of top-notch DJs and artists who either came through LA on a regular basis or who chose to stay was pretty staggering. Between them and the very considerable home-grown DJ talent that was also coming up, it meant that there was absolutely no shortage of quality dance entertainment in the city.

You could go to a place like Atmosphere at the Viper Room to see all-world headliners like Oakenfold or Digweed, and then find a hole in the wall where the next groundbreaking talent was honing their chops. The same thing was taking place at raves—yeah, you’d see the Chemical Brothers or the Crystal Method, but you’d also see some guy that you’d never heard of, who was so good, you’d have their demo CD in your hands by the end of the night.

Because of this, and other factors, the Southern California 90s rave scene often felt like a big extended family. Fellow fans became distant cousins who you’d see two or three times a year at gigs, which was important since social media as we know it today didn’t exist back then.

So yeah, I miss those days. It was an incredible, unique era, and we all knew it, even though everyone else was utterly clueless about it.

What was one of your favorite stories during your time at the underground raves?

Ha—there are too many to name! Seriously, just one? Well, one of my favorites was the night in ’99 when DJ Sandra Collins and I were sort of kidnapped by Superstar DJ Keoki.

I made a storytelling video about it a number of years ago, back in my clean-shaven days.

You’ve said you’ve, “Always felt that the time period of the rave scene is one of the most critically overlooked periods in American pop culture,” why do you feel this is the case?

The rave scene never got the mainstream respect that other genres of music got. This was partly because the rave scene was a genuine grassroots movement, with few real ties to the bigger entertainment business. It wasn’t dependent on the record companies, though many in the scene, particularly the artists, certainly wanted the majors involved. It was outside the system and that confused and irritated many inside the system.

The big music magazines and music programs made practically no effort to cover the early rave festivals, and few albums were reviewed, which meant that electronic music artists were never celebrated and publicized like mainstream artists are.

And, while the rave scene had its early underground years closely resemble those of hip-hop, the latter enjoyed the nearly universal support of African-American culture (and with it, African-American media and record companies), which would ensure its growth and expansion over the years.

Another factor was the MDMA controversy in the media and the spillover of drug blame that would incorrectly tie other drugs to the scene. There was never any serious opiate or cocaine problem in the rave scene. Ketamine was around, but its prevalence was small, percentage-wise, and GHB was located more in the mainstream clubbing scene as a date-rape drug.

However, the MSM jumped all over the MDMA issue, in a predictably scaremongering, over the top way: “Do you know where your children are???” One of the things that eventually arose from this noxious atmosphere was a totally pointless piece of legislation called the RAVE Act, which was sponsored by senators Chuck Grassley and Joe Biden. It caused some major league headaches for some of the major figures in the scene, most notably “Disco Donnie” Estiponal, who was eventually able to beat the bum charges against him.

I mentioned earlier that I often compare the rave era to the Jazz Age because there are a lot of parallels. Both genres started out being regarded by mainstream society with suspicion and curiosity. Both had their vices: the Jazz Age’s bathtub gin, and the rave scene’s MDMA.

The Jazz Age had its speakeasies, and the rave scene had its after-hours clubs. In each case, the music was dance-oriented, based on African-American rhythms. The difference was, in the rave scene, no Duke Ellington’s or Ella Fitzgerald’s came to the forefront, and unlike in the Jazz Age, few in the record business thought to go looking for them.

So, jazz eventually became a vital part of the great American songbook, while electronic music never got the boost it needed to enjoy the same status. EDM is still having to deal with the baggage as a result.

Why do you think EDM has still not been recognized as a legitimate music movement in comparison to others such as Hip-Hop, Rock, or Jazz?

There were three major reasons back in the day: the mainstream music media, the radio stations, and the recording industry…and sadly, not a lot has changed.

When electronic music began to spread across the country in the 90s, the music and the culture did not fit neatly into the mainstream media paradigm, and so the various bodies involved had great difficulties coming to terms with it.

For the music media—meaning the print and TV media of the day—the rave scene remained an elusive subject that most couldn’t wrap their fingers around. This was partly because rave promoters felt little need to engage the press because their parties were already swelling in attendance on their own.

The coverage of the rave world by the heavyweights, like Rolling Stone, SPIN, Billboard, and others, ended up being a fraction of that devoted to the other more “legitimate” genres of music that populated the charts. Also, since the rave scene had no obvious stars or celebrities for the media to latch onto and exploit, the media wrote and broadcast little about the scene outside of the drug issue.

The irony was that this was an old tactic used by the conservative press against the counterculture movement in the 60s, and now the practitioners of that former counterculture were using the exact same tactics against their children in the rave scene.

The major record companies were of little help, as electronic music artists didn’t fit into the longstanding categories within their organizations. Eventually, they created this artificial new category called “electronica”, which practically nobody in the rave scene took seriously, even after some of the labels had signed major acts like the Prodigy. They had no idea how to market their own acts because they were so isolated from raving culture that they didn’t understand it.

The radio stations were no better, for the most part. Again, the lack of celebrity artists meant that they had little clue about what tracks to play, let alone get behind. One of the crucial links in the radio chain of command is the syndicators—the companies that funnel the music from the labels to the stations themselves.

In the mid-90s, the biggest syndication network in the country was Clear Channel, which owned American Premiere, a company that I happened to be writing for at the time. At Premiere, I watched the weekly CDs filled with new singles and programming that would go out to the radio stations, and two things became quickly apparent.

One, electronic music was having a huge problem with categorization, as it didn’t really fit in at either pop or rock stations…and two, the new “electronica” category devised by the labels was no help at all.

There were only two 100% electronic music stations in the country in the 90s, and both of them went under within a year of operations. That’s not enough to maintain any sort of market share for your music. Ultimately, the labels found little reason to keep releasing electronic music that wasn’t going to get played.

Another thing that should be brought up is the secretive nature of electronic music festival operation, a nature born out of necessity. Because the rave scene has been screwed over time after time in the press over the course of two decades, companies like Insomniac and Ultra have had to batten down the hatches and release a few details about their operations to the general public as possible.

They’ve learned through experience that the less information that gets out there means the fewer things can be used against them in the public arena. It’s an unfortunate situation, but when you’re being consistently pilloried by a press that’s made it clear that they have little or no intention of reporting about your events fairly, you’re gonna do what you have to do.

This is a major reason why virtually no mainstream media is allowed at these festivals, and all the details are released through publicists and social media. Of course, when the MSM can’t report on an event on their terms, they’re much less likely to deliver a fair or positive message about what’s going on. And thus, the situation continues.

Yet another factor is that there’s been very little taught about electronic music—and especially its history—at music schools and major universities. This is partly because the genre is so new that the official histories about its origins are still being written, so most of what’s currently being taught has to do with music production.

There are a few schools that have introduced courses that address the music’s background, and I have actually spoken to classes at some of these schools. As time goes on and the genre continues to mature, doubtlessly the number of schools offering such courses will increase, which will help things somewhat.

As the decades changed the camera equipment evolved, how did technology change the way captured rave moments?

It changed a great number of things throughout the entire photographic process. First of all, as far as media is concerned, it sped up the whole thing to nearly instant content generation. In the pre-Internet film & print media days, the process was much slower. From the time that a photograph was taken to the time that the photograph appeared in a rave magazine, usually, two months or so had passed.

This was entirely due to the long amount of time it took to write, assemble and print a magazine, and then distribute the magazine to the greater public across the country. A major magazine like Rolling Stone could turn stuff around faster, but of course, rave oriented material almost never appeared in the likes of Rolling Stone.

Now, entities like Insomniac or AEG can generate their photographic and video material live, with an instant global market that far exceeds what the print magazines ever reached. Just as importantly, they can monetize that to generate a return, something the old rave scene never enjoyed.

The transition from film to digital means that the photographer has a great deal more options when working in the field, options that simply weren’t around in the analog era. Today you can shoot and edit images on the fly, changing ISOs, white balances, color balances, and file destinations.

You would need several different types of film and filters to do the same thing with film photography. You used to have to wait for the film to come back from the lab; now you can transmit pics directly from your camera to an editor or a server.

You can shoot a lot more because today’s memory cards can hold massive amounts of data. Many of today’s cameras can command multiple flashes remotely, so your lighting options are a lot wider as well. And of course, the film cameras had no video options at all.

The transition definitely changed the way that I shoot events, because of the quantity factor, mainly. When shooting on film, you’re strictly limited by the number of frames of film left on the roll you’ve got in the camera. And of course, you can’t open the camera until you’ve gone through all the frames on the roll, and when you have, you have to unload that used roll and put a fresh one in the camera.

So, you’re forced by the nature of the situation to become much more economical in your shooting. You can’t just keep the shutter button pressed down until you eventually end up with a usable picture, as you can with today’s digital cameras, because you’d run out of film very shortly.

So when I was in the film world, I was often very slow and deliberate in my shooting, because I was on a budget and didn’t have the funds to carry around hundreds of rolls of film. Nowadays, I can burn through memory cards with the best of them if I need to.

Also, storing and archiving large quantities of the film can be a major chore. I literally have bookcases filled with tens of thousands of slides and negatives from those days. To this day, I thank God that I had enough foresight back in the day to create a filing system that actually worked.

External hard drives have mostly replaced these today, and for good reason: they’re relatively inexpensive and easy to operate. Yeah, you have to back things up multiple times on multiple drives (or somewhere in the Cloud), but having that quick access is really important, particularly when you’re talking about archives.

Lastly, the digital revolution means that you have more options in post-production than the past generations of photographers and graphic designers ever did. You can do literally almost anything with your images, especially when you’re shooting in RAW.

Photoshop, Lightroom, and other image editing platforms have changed the game completely, not only giving the photographers greater control over their images but also speeding those images out to outside media platforms.

If you were recommending equipment to a novice rave photographer what five pieces of equipment are a must?

Assuming that we’re talking about either a DSLR or mirrorless camera with a bayonet mount lens system,

- A good camera body that has both a wide dynamic range and a good high ISO count.

- A bright, fixed 50mm or 35mm lens, f/1.4 or f/1.8.

- A high-quality flash.

- A good, bright mid-range zoom lens, either 24-70mm or 24-105mm. Should be f/2.8 if possible, f/4 as a second resort. (NOTE: Don’t worry about ultra-wide or fisheye lenses yet. Learn the basics first.)

- A top-notch image editing program, such as Photoshop or Lightroom. A great deal of what you’re going to be doing is post-production, so a good editing program is crucial. There are other program options for folks who aren’t fans of Adobe’s subscription policy.

When shooting in the club what settings and techniques did you employ to achieve your famous movement effect?

I developed a number of techniques to reproduce that sense of energy that was flying through the room at the time. Some of this involved movement, primarily of the camera during a long exposure.

When you keep the shutter open and move the camera, you produce a swoop or blast of light. When you change the swoop of the camera into a rotation, you produce a swirl. I used this swirl to illustrate the vortex-like energy that seemed to exist during particularly intense parts of a DJ’s set.

Another technique I used was the use of multiple flashes in the field. I used these flashes primarily in two ways. The first one was setting off the flash multiple times during a long exposure, to create a stroboscopic effect that illustrated or exaggerated the motion of the subject.

This was particularly effective when I combined it with a swirl. It made normally stone-still DJs come to life in a high-energy interpretation of their set. I also used it in a “playing card” technique, where I would shoot a vertical picture, pop the flash, rotate the camera 180 degrees, and then pop the second flash before closing the shutter.

The other way I used flashes was to put different colored gels on each of them, so as to create colorful two-tone (or in some cases, three-tone) lighting. This worked out great because it gave the photo more depth, and also because the bright colors made by the gels would usually mesh in well with the special effects lighting at the party.

These would be shots that I would spend a few minutes beforehand setting up, after examining the special effects lighting, the projections, and the stage setup itself. It was a case of figuring out what colors worked best with everything else that was going on.

Sometimes I would add on even more light and color with light painting, or even laser painting. Or, other times I would just strip everything down and just leave the camera shutter open, to let the picture paint itself, so to speak.

With so many elements out of my control—the party’s lighting, projections, lasers, etc.—that’s sometimes what it felt like for me, particularly in the early years. I sometimes felt like I was the conduit for the image, and not really its creator, especially in the case of my abstracts.

How did you transition from freelancing to shooting for Getty Images?

Through the back door. It’s the old Hollywood adage: it’s not what you know, it’s who you know. In this case, a friend of mine who was a Getty shooter was leaving the company, and he recommended me to his superiors, who soon became my superiors. It was the rare case of starting at the top, at least as far as photo agencies are concerned.

When I started out with Getty in 2004, I had two missions: (1) to fit into the celebrity photo industry standard, and (2) to bring as much of my old rave approach to this very mainstream media outlet as I could.

The first mission was for obvious reasons—I had to shoot a lot of red carpets, and I needed to learn the etiquette of shooting celebrities on the line. The second mission was a tougher one, for there were very few electronic music events of any kind being covered in the entire country at the time by Getty, or any other major photo agency.

In fact, Getty’s LA office wasn’t even aware of gigs like EDC or Nocturnal Wonderland, despite the fact that they were bringing in tens of thousands of people…right there in the city, in EDC’s case. I was the one who brought these events to Getty’s attention, and when my editors first saw the pics I sent them from EDC, they couldn’t believe what they were seeing.

Now, when there’s a major electronic music event happening in LA, I’m usually the first one Getty asks to cover it. So, it’s heartening to know that I’ve been able to do my bit to get this culture more out to the people, from the inside.

When you transitioned from rave to celebrity red carpets was there anything you had to do to adjust to the new environment to be successful?

Celebrity stuff is often a lot more formalized and regimented than party pictures. You have to deal with publicists, managers, and sometimes temperamental artists. You often have very little time to work with—if you’re on the line at a step-and-repeat, you’ve got just seconds to line up your subject, get good eye contact (crucial!), and show them off the best you can.

If you’re lucky enough to have a proper photoshoot with an artist, you very often only have a few minutes to work with, so it really helps to visualize beforehand. This came in very handy for me when I got the call to photograph Brian May of Queen at Book Soup a number of years ago.

He was doing a signing for one of his books on stereo photographic art, and I knew I’d only have a very short amount of time with him. I’ve done several shoots at Book Soup, so it wasn’t hard to figure out where I was going to put Brian, and how I was going to light him. And fortunately, Brian and I had actually conversed via email a few times beforehand, so I got hold of him and told him that I would be at the signing. Lo and behold he was ready to go when he arrived, and we banged it out in a few minutes. Great guy, too.

The other main thing I had to adjust to was putting up with the behavior of some of my colleagues from other agencies. Without going into specifics, let’s just say that like in any other line of work, there are some very angry and bitter people in the celebrity photo business. And, when you’re stuck standing next to them on the line for a number of hours, things can sometimes get unpleasant. This is where you really have to learn to hold your tongue and not let things get under your skin. A number of them don’t shower very often, either.

Don’t get me wrong, there are some fantastic people in the industry. There are photographers and editors whom I’ve known that have been a joy to work with. Among my best industry friends are photographers from competing agencies, who I know will still have my back if shit goes down, and vice-versa. But the bad ones…let’s just say that a silver lining of this virus situation is that I haven’t had to see them for four months.

How did the idea of The Ravers Stories Project come to you and did it achieve your expectations?

“The Raver Stories Project” came about because I wanted to put out a second book, but I didn’t want to do another photo book like “DANCEFLOOR THUNDERSTORM”. I wanted to put out something that explained why the rave scene meant so much to the people in it.

This is something that many outside the scene just didn’t get: what it was that drove these people to do what they did, whether they were ravers, artists, or promoters. It was peeking behind the curtain, to show what was going on in this secret rave society.

I put out a call to the electronic music community in 2016, asking people to submit one story about an event or incident in the rave scene that was meaningful or memorable to them. Everybody has at least one good story in them, and ravers have traditionally not had the means to tell those stories.

The response I got was fantastic, as I received stories from around the globe, from people in both the original rave and EDM generations. There were stories from as far back as the original acid house explosion in England in the late 80s, along with stuff from Burning Man, Ministry of Sound, Winter Music Conference, and more.

The great thing was that I was able to capture the scene—and what was important to the people who populate it—from multiple points of view. The diversity within the scene demanded it; having just one viewpoint or interpretation of it would have been absurd. It accurately told things which you never would have found on the news, or in most music papers. So in that respect, it was very successful.

What projects are you currently working on?

Actually, with lockdown, the main thing I’ve been working on has nothing to do with electronic music. It’s a photo fantasy blog called #KAIJUINLA, which chronicles the adventures of Japanese monsters and giant robots across Los Angeles.

Since everything entertainment-oriented in LA has been shut down, I’ve obviously had to find something to do, so I take these little kaiju action figures around town. There are pics in there of Godzilla on Hollywood Boulevard, Gamera on Venice Beach, that sort of thing. It’s helped keep my shooting skills sharpened, in a creative way.

I’ve also been involved in shooting the many Black Lives Matter protests that occur pretty much daily here in Los Angeles. I’ve put several galleries from these events up on my website. Click here to check them out. I’ve also put up a couple of video photo pieces on my YouTube channel here.

Photographing political events—particularly revolutionary ones—is obviously very different from shooting at a party. However, life prepares you in strange ways sometimes, because at a recent BLM rally at LA City Hall that I covered, a tribal dancing circle was assembled, and I found myself shooting wildly whirling and contorting dancers, much as I had back in the rave days. So, there you go. Click here to check out the gallery.

If you could give advice to budding rave photographers what would it be?

Learning the business of photography is just as important as the making of imagery, if not more so. This has never been truer than today, when photographers are taken advantage of left and right—by the media, by clients, by thieves, and others.

Most photographers who don’t learn the business and legal ends of things are not going to be in business for very long. Your schools that teach photography will likely not have business courses in their photo curriculum, so it’s going to be your responsibility to educate yourself about how to make money from pursuing your passion.

- You’re not going to make much money in the beginning. Don’t let yourself be discouraged by this. Plan for the long haul.

- Build and maintain relationships with members of the music media, promoters, and artists. This is how you’re going to get access to events and build your portfolios. Artists who haven’t broken yet are great for this.

- If you can attach yourself to a major artist, do so and never let go of them. Make yourself indispensable to their marketing.

- Study other photographers, but don’t copy them, unless you’re doing a photo exercise to educate yourself technically. Find your own style.

- There are loads of great photography websites out there. Find them and peruse them regularly.

- Shoot in black & white when you can.

- Update your portfolios constantly.

- Copyright your images.

HAVE YOU SEEN MICHAEL TULLBERG WORK? SWIPE UP TO COMMENT BELOW

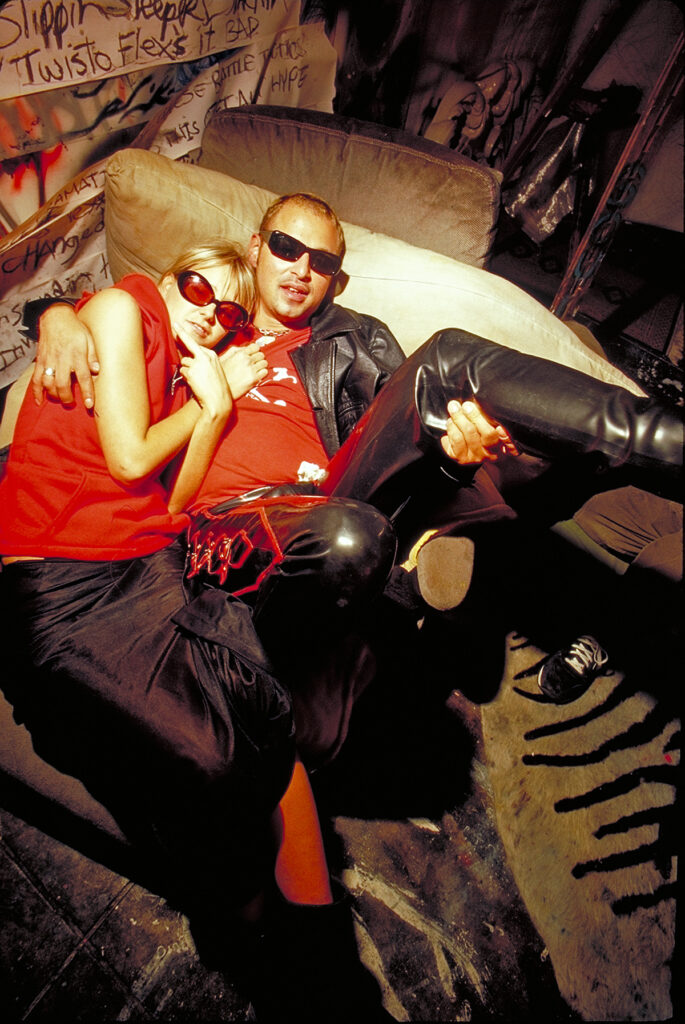

A truly candid moment! Meet Sandra Collins and Superstar DJ Keoki, two of the truest characters in the electronic music world. I shot this at an after-party in Keoki’s old warehouse/studio complex in downtown L.A. in March of 1999, where Keoki brought us after practically kidnapping a whole bunch of us after one of Sandra’s gigs! We all got there around 4:30 AM, whereupon Keoki said to me, “Dude, get out your gear and start shooting!” I asked him, “Are you sure about this? After all, this is your LAIR, man!” He simply smiled and said, “No problem dude, I trust you.” Considering how temperamental the man can be at times, I was extremely flattered…and was all too happy to oblige him, as you can see! Yeah, it’s a rough job, but somebody’s gotta do it…

No Comments